By Christine Burns

Hydrographic surveying continually evolves to improve safety, efficiency, and accuracy in data collection. From using side scan sonar equipment during hydrographic survey response efforts following air disasters in the late 1990s, to recent hurricane response efforts to re-open ports to maritime commerce, our science always strives to be cutting edge.

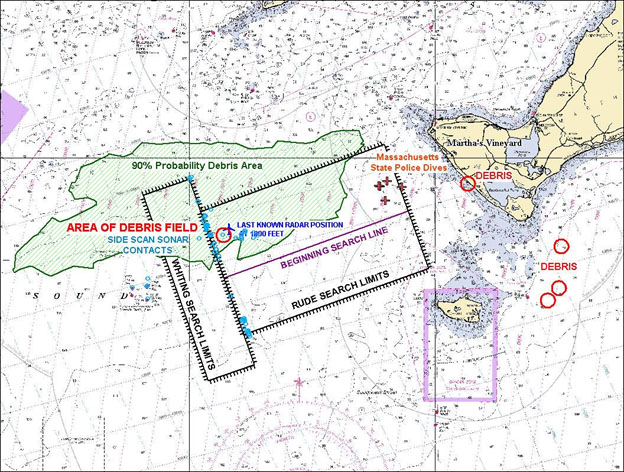

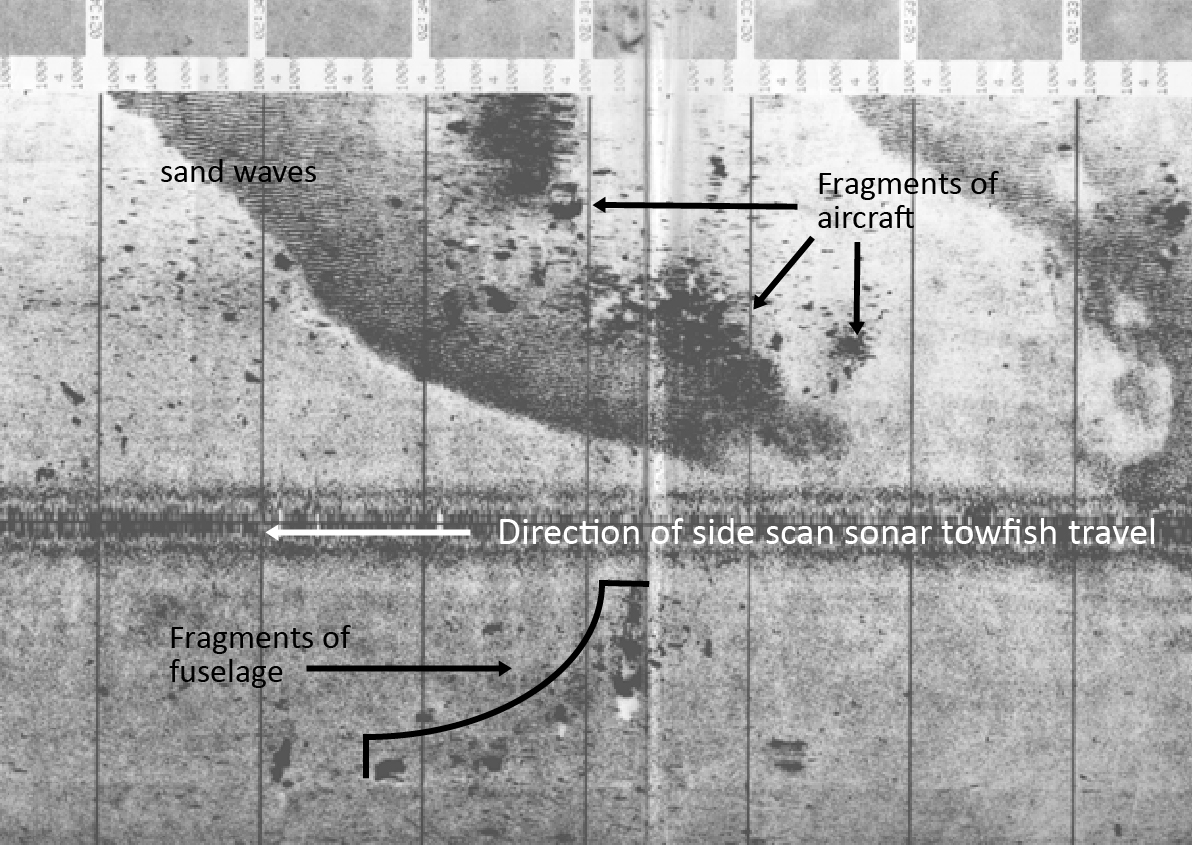

Today marks twenty years since John F. Kennedy Jr., his wife Carolyn Bessette, and his sister-in-law Lauren Bessette perished after their Piper aircraft crashed in the Atlantic Ocean near Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., on July 16, 1999. At the request of the U.S. Coast Guard, the NOAA Ship Rude was called from its survey grounds in Long Island Sound, N.Y., to assist with search operations to locate the missing plane. Since little was known about the location of the plane crash, the Rude began an expansive side scan sonar (or object detection) survey in the waters surrounding the Martha’s Vineyard airport. Two days later, NOAA Ship Whiting arrived from its survey grounds in Delaware Bay to assist with the search. After three days of surveying, Rude discovered a suspicious object on the seafloor which was later confirmed to be the missing plane.

While it might be surprising to learn that NOAA ships were called in as disaster responders, this was not the first time NOAA assisted with air disaster response and it was not the last. The first time a NOAA vessel assisted with this kind of disaster response was July of 1996 when NOAA Ship Rude assisted in the search for TWA Flight 800 off the south coast of Long Island. Based on the expertise demonstrated in 1996, NOAA was asked for assistance in 1999 in the search for the John F. Kennedy Jr. crash site. Just four months after, NOAA Ship Whiting was again called, this time to locate Egypt Air Flight 990. NOAA’s survey ships have become an integral part of maritime disaster response from re-opening ports after hurricanes to damage assessment surveys after oil spills.

Why is it that NOAA ships were called upon to assist with these historic air disasters? How is it that they were so prepared to help in these times of crises? According to Rear Adm. Sam DeBow (NOAA, ret.) who coordinated NOAA’s involvement in the John F. Kennedy Jr. aircraft search, “NOAA was well equipped to respond to these air disasters because we do survey work 10 months of the year. This is our job. This time we’re just looking for something a little different.” Although not designed for air disaster response, NOAA used their experience and surveying knowledge to help in these times of crises. In addition to being highly experienced, the NOAA ships had cutting-edge technology for the time. This allowed NOAA to provide precise position information for all objects located on the ocean floor.

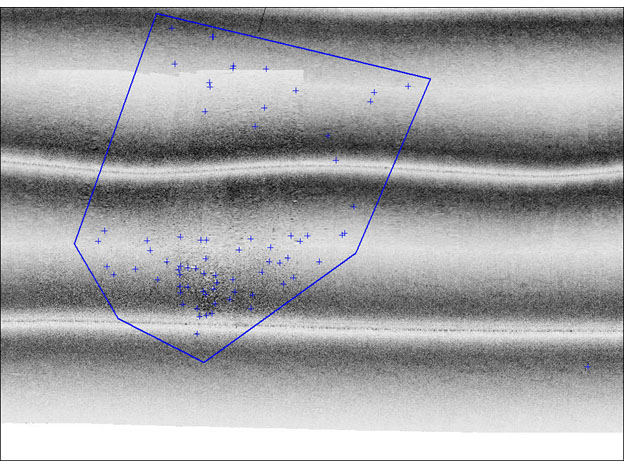

Twenty years have passed, and NOAA is still using cutting edge technology to survey the ocean floor. While great advancements in technology have been made over the last twenty years, survey equipment has fundamentally remained the same. What we can achieve using sonar data, however, has changed dramatically. In the late 1990s when NOAA ships Rude and Whiting were surveying, scientists predominantly worked with 2D side scan sonar. They collected the images with the side scan sonar and then had to hand mosaic or stitch the images together. From these images, they identified the potential locations of debris and sent out a list of latitude and longitude values for each point. This was a cumbersome process, requiring close attention to detail.

Now with the advancements in technology and computers, many of these steps are easier. While the fundamental process has not changed, the quality and resolution of the data certainly has improved with time. Today’s side scan sonar and multi beam systems can collect more accurate data at faster speeds. This allows the ship to cover more ground in a shorter amount of time. Today NOAA ships can collect more than a gigabyte of data per hour with side scan sonar.

Currently, NOAA survey teams use side scan sonar and multibeam echo sounder technology to re-open ports following hurricanes, including recent events such as hurricanes Florence and Michael in 2018 and sequential hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria, and Nate in 2017. NOAA’s regional navigation managers and navigation response teams stand ready to respond to a host of emergency incidents in the coastal waters of the U.S.