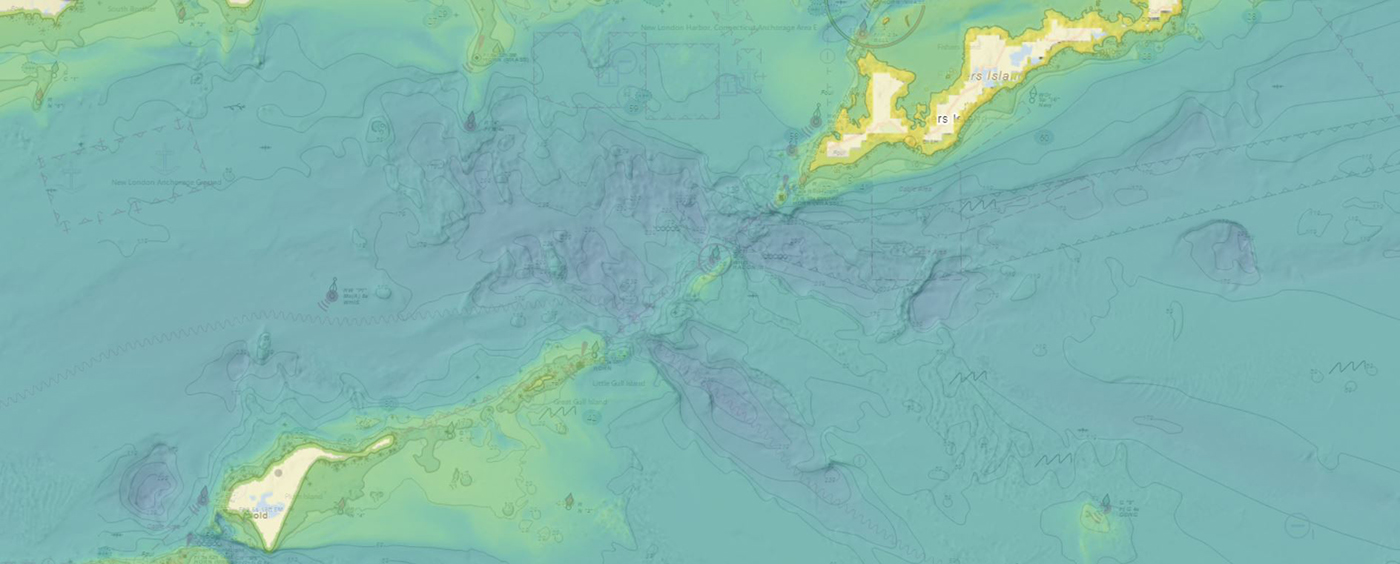

We are pleased to announce the availability of new seafloor mapping data to support energy infrastructure planning in the Long Island Sound!

This survey is the result of a Coast Survey partnership with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CTDEEP) through NOAA’s Brennan Ocean Mapping Fund opportunity, a program that allows non-federal organizations to co-fund projects of mutual interest utilizing NOAA’s contracting and data management expertise. NOAA selected this project in the FY2024 round of the matching fund opportunity.

Continue reading “NOAA releases Long Island Sound survey data to support electric power cable planning”